Human mobility data, which shows an individual’s movement as measured by their activity on smartphones and social media platforms, has reshaped emergency management and response. These data can give response agencies and local governments near real-time information on population movement patterns before, during, and after an emergency event takes place. Equipped with this powerful data, responders have new opportunities better understand the dispersal patterns of populations affected by a crisis, and can deploy resources and coordinate more efficiently.

The seventh meeting of the Disaster Mobility Data Network (DMDN), hosted by CrisisReady on January 27, 2022, convened a roundtable panel to discuss the usage of mobility data in emergency contexts. Featured discussants included Phil Beilin, Geospatial Data Analytics Cell Manager at FEMA Region IX, Melissa Schigoda, Director of the Office of Performance and Accountability at the City of New Orleans, Dag Brynjarsson, Program Manager of Disaster Preparedness and Response at NetHope, and Abigail Browning, Chief of the Office of Private Sector and NGO Coordination at California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES.)

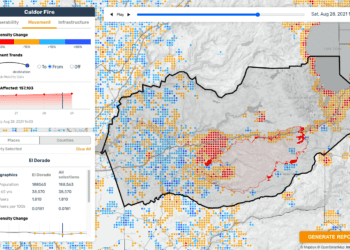

It was widely agreed upon by the discussants that human mobility data serves an important and highly useful function in emergency response. This is supported by CrisisReady’s work with them in producing rapid situational awareness reports by the Disaster Situation Reports team that show population movement dynamics before, during, and after an emergency event takes place.

To further contextualize the use of mobility data in response efforts, Direct Relief and CrisisReady’s Andrew Schroeder shared four major challenges that arise from the incorporation of these data streams in emergency contexts. These challenges, posed as questions, are as follows:

- How do teams – consisting of researchers, data practitioners, and data analysts – produce timely analyses out of big, often overwhelming, data sets?

- How do these teams develop a set of relevant questions before conducting analyses, managing the delicate relationship between standard response questions and bespoke questions that pertain to a specific event?

- How do these teams effectively work with partners across organizations, and how do these organizations communicate analyses internally to support decision-making?.

- How do these teams understand, represent, and communicate the uncertainties of human mobility data without undermining the authority of the data? In other words, how do researchers treat uncertainty responsibly?

Jennifer Chan, Associate Professor and Director of Global Emergency Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, discussed the concept of translational readiness and how it can be used in response efforts to solve these challenges.

In its broadest definition, translational readiness is a team-based approach to using human mobility data to strengthen the questions, solutions, and the understanding of relevant problems throughout an emergency response. She explained that it’s important to approach translational readiness within the framework of context, purpose, and people.

Defining the unique context of an emergency event and how it impacts individuals is an important first step when incorporating translational readiness into a response effort, said Chan. Once this question is answered, it becomes easier to understand the broader purpose of the data and how it can be used to achieve desired outcomes. Finally, the consideration of the individuals and responders impacted-by and tasked-with managing emergency events helps ensure that data-driven response maintains a people-centered approach.

Rakesh Bharania, Director of Humanitarian Impact Data at Salesforce and a participant at the DMDN meeting, brought up how to best scale the impact of human mobility data within emergency responses. Bharania explained that long-tail crises, such as climate change, are emergencies that require data-driven, multilevel,and multiorganizational responses. Despite this, there is a dire lack of data literacy – the ability to interpret a data product to inform decision making – in emergency response as it currently stands. In order for mobility data to make an impact at scale, he recommended facilitating partnerships between research institutions, like CrisisReady, and larger, globally-focused response organizations, such as the International Association of Emergency Managers. According to Bharania, this could improve data literacy among first line responders and those operating at the incident command level, where efforts tend to be very tactical.

Abigail Browning agreed with Bharania’s statements, claiming that the operational and tactical areas of response tend to focus primarily on attending to the immediate impacts of a crisis as quickly as possible. In doing so, valuable data – which could be used to increase efficiency throughout response efforts – are often unused or disregarded until later in the response. This may be attributed to the bureaucratic nature of emergency operations centers (EOCs) and the limited resources available to train responders on data analytics, explained Browning. She said that this issue could be solved by updating budgets and reallocating resources at EOCs to build up IT departments, which would consist of data analysts with expertise comparable to those at private sector technology companies.

Dag Brynjarsson commented on the individuals who comprise EOCs at both the local and national levels. He said that many of them are used to managing crisis events by hand, which feeds into the issue mentioned by Browning. This makes it difficult to promote data-driven decision making in emergency planning and response, not only because of the need for timely action as explained by Browning, but because of the rigid precedent established by agencies in the past. Brynjarsson explained that more people need to be involved in response planning to review data products, interpret them, and communicate insights to their organization’s operational units.

Melissa Schigoda brought up the issue of overlapping disaster events and their impact on response efforts. She said that during such events, the neatly-defined organizational models laid out by response agencies tend to become disarranged. During these circumstances, responders may be tasked with managing two or more coincident emergency events at once, putting a significant strain on their time and ability to respond to a crisis efficiently. Additionally, sporting or cultural events, where regional populations undergo sudden and drastic influctuations, adds a significant burden to tactical and analytic response procedures. These are important aspects to consider when developing an appropriate response, said Schigoda, but it becomes difficult to contextualize them with human mobility data when there are so many other important factors to consider.

Phil Beilin then turned the conversation to recovery, where he sees a significant opportunity for the use of mobility data. He explained that the data functions as a sort of evolutionary tool, where some pieces of data are used for immediate response and some feed into derivative products created as an event evolves. Early sets of mobility data become an important source of information as response turns into recovery, he said, and understanding the full breadth of the data in these contexts allows agencies to capture important data that may be overlooked in the early phases of response.

Communicating Data Usage in Response with the Public

Communicating how the data is used in response efforts is an ongoing, often contentious, topic in the realm of emergency management. Abby Browning said that in her work at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES,) it would not be communicated unless her team was directly prompted to disclose this information. She explained that this is due to the controversial nature of using such data sources in a governmental capacity, regardless of its utility in emergency situations. Many communities that her department oversees, especially those in rural areas, have concerns about the government’s use of personal data and may automatically assume the data is being used in a coercive or inappropriate way, she explained.

Phil Beilin attested to the sensitives around mobility data, but said response agencies have a responsibility to clearly communicate to the public how the data is used, its implications, and it’s added benefit to emergency response. He mentioned that explaining how human mobility data compliments other, less personal datasets, and that it is one of several streams used in decision making, is a way to maintain transparency and build trust with local populations. There needs to be multiple strategies in how these data usages are communicated, he added, and agencies ought to develop multiple products that convey this information to different cultures, age groups, and regions in relevant ways. Andrew Schroeder agreed with Beilin’s statements, saying researchers need to be mentally agile to adjust their means of communication and develop multi-channel reports that are useful for various stakeholders involved in an emergency situation.

Digital Equity and its implications in data integration

U.S. Digital Response (USDR,) a non profit organization that helps governments and organizations respond to the community needs during and after a disaster event, hosted a webinar in Spring 2021 that brought together experts in government and technology to discuss how digital technologies can play an important role in crisis management. In an article that summarizes key takeaways from the webinar, the topic of communication and trust is discussed. The article notes that “In a culture that’s accustomed to immediacy of information and has become highly politicized, building and maintaining public trust [is] a major challenge for governments at all levels across the country.”

During USDR’s webinar, Mayor of Seattle, Washington Jenny Durkan, who played an important role in directing the city’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasized key elements of deploying effective, trustworthy communications during a crisis. She said that establishing unity of voice across all involved parties at the outset, remaining grounded in the science and data, and being honest about what the data can and can’t tell us is of chief importance. This echoes the comments made at the beginning of the DMDN meeting by Andrew Schroeder and Jenifer Chan, namely about how research teams should handle uncertainty responsibly and consider the needs of end users when developing and disseminating analyses.

“Without a digital response, there’s no response these days,” Mayor Durkan said during the USDR webinar. Durkan’s statement gives credence to the comments made about the utility of mobility data in emergency contexts throughout the DMDN meeting. However, it’s important to note that digital responses can naturally create divides within the communities they aim to support. Phil Beilin mentioned that if agencies and local governments adopt a data-driven, digital response, the onus is on them to maintain digital equity throughout the entire emergency event.

Melissa Shigoda said that during crisis events in New Orleans, 311 calls are typically made from wealthier neighborhoods in the city. This trend highlights the disparities between communities of differing socio-economic standings in regards to information acquisition and accessibility during an emergency event.

Shigoda brought up another significant issue: when looking at baseline census data, impoverished and underserved areas of the city are often underrepresented. She noted that many of the individuals in these areas lack access to smartphones or wireless connectivity, which exacerbates inequalities during emergency events. These become chief concerns when incorporating novel data streams, especially human mobility data, into a response because it runs the risk of underrepresenting marginalized communities that may be disproportionately affected by large-scale crisis events.

We thank each of the discussants and participants for joining the seventh Disaster Mobility Data Network (DMDN) meeting and for sharing their insights and expertise. DMDN meetings are hosted every month, with a new topic being discussed each session. For more information on upcoming DMDN meetings, please visit CrisisReady’s events page and follow us on Twitter.

For more on the DMDN Meeting 7, follow the link provided below: